First up a bit of boasting. I just walked 799km in 31 days. I’m quite proud of myself. I also had the luxury of stepping away from the world of teaching for a whole month. And not just away from teaching – from the real world itself. When on a long distance trek there are no real decisions to make, you simply wake up, walk, eat, sleep and repeat. Despite this, it took me a good week or so to get out of the habit of looking for things to be stressed about. What if my feet hurt? What if it rains? What if I can’t find a cash machine? What if the next hostel also doesn’t have WiFi and I can’t Facebook my fabulous photos? And what about all those people looking at my fabulous Facebook photos thinking teachers have it easy? All these long holidays, who are they to complain about their heavy workloads? Actually, I don’t think my friends think like that and even if they do I don’t really care, but teachers do have a reputation for making a meal of it, and that is very unfair.

Most teachers I know are freelance, or they have contracts which run October to June, which means it’s almost impossible to survive the year without taking on some sort of summer job. Like any profession, there is a huge focus on professional development with many teachers taking on extra work or additional courses to enhance their prospects. I’m currently working full time on this refugee project, setting up my first CELTA as main course tutor and completing an online course in online tutoring (the IHCOLT if you’re interested). I’m also trying to keep up this blog, enjoy the short time I have in Lebanon, and right now trying to catch up with everything that’s been going on in TEFL while I’ve been off the radar.

Luckily, I stumbled upon a lovely blog post from Emily Hird, who had helpfully summarized the what’s hot and what’s not of YL nicely for me (read her post here). It’s all about current trends in young learner education, all of which require skillful handling by the teacher. It’s a pretty big task teaching a foreign language to a small child, and on top of that we need to remember to develop life skills, creativity, innovation, social values… the list goes on. I love how much good intention there is in primary teaching. A lot of teachers stick to adults and teens, not that those classes can be called easy, but it is generally accepted that to teach primary you need to put in a lot of effort and develop a totally different skill set. Many (admittedly not all) of the essential skills mentioned by Emily are well developed by adulthood, but to incorporate them into the primary classroom can be daunting. These skills call for an increase in communication between students, more collaboration and learner autonomy and a relinquishing of control from the teacher, all of which is brilliant and all of which can lead to classroom management nightmares.

Once you have classroom management under control it’s astonishing how much you can achieve in a young learner classroom, and just how mature young children can be. It’s a joy to see groups of children working on creative projects, supporting each other and taking responsibility for their own learning. There are many ideas for behaviour management, commonly reward systems, which I’m not going to write about here. What I want to focus on is parental involvement. Not in terms of meetings, messages, reporting or responding to problems – things which are time consuming and potentially reactionary. I want to share my recommendations for maintaining open channels of communication with parents via a few time-efficient strategies which have worked for me. When students know you have access to their mums and dads the stakes are suddenly raised and you can often turn your attention to teaching rather than crowd control. Having open communication with parents can also have a dramatic effect on the progress and achievement of your students. When parents show interest in what their child is learning and know how to help practice language at home, the results in the classroom are noticeable.

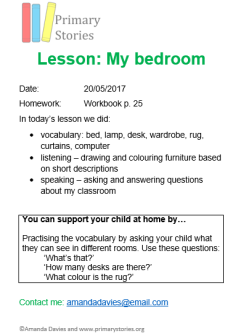

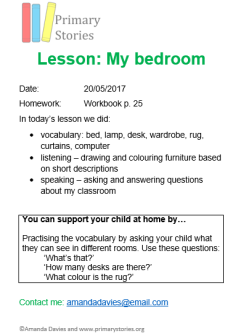

- Lesson summaries

Private English lessons are expensive so parents understandably have high expectations and want results. The age for learning a foreign language at school is getting lower and lower and English is seen as a priority to give children a head start in life. When parents know what their child does in class, there are two major benefits. Firstly, they have a deeper understanding of what to expect, e.g. their 5 year old is not going to be having fluent conversations in English after a couple of lessons. Secondly, a large majority of them actually want to help, and when parents practice lesson content at home with their child, there is much less work for the teacher. I always use lesson summaries, which you can download here, as a way of keeping parents in the loop. I put the main lesson content along with the homework task, and a short description of what parents can do at home to further support their child learning English. Not too much detail is required, and in fact I always prepare mine when I’m planning the lesson, so if I’m not sure how much of the lesson I will get through I play it safe and stick to something I know I will cover. I can always add things to the next lesson summary if I miss something important. I use these for all early years and primary students, but they work particularly well for the younger students up to the age of about 10. Older students are more capable of remembering and telling their parents what they learnt, particularly if you use Assessment for Learning strategies such as WALT, or Can Do Statements. I give out my summaries as the children leave the classroom, that way they make it straight into the hands of their parents instead of disappearing into school bags never to be seen again.

Private English lessons are expensive so parents understandably have high expectations and want results. The age for learning a foreign language at school is getting lower and lower and English is seen as a priority to give children a head start in life. When parents know what their child does in class, there are two major benefits. Firstly, they have a deeper understanding of what to expect, e.g. their 5 year old is not going to be having fluent conversations in English after a couple of lessons. Secondly, a large majority of them actually want to help, and when parents practice lesson content at home with their child, there is much less work for the teacher. I always use lesson summaries, which you can download here, as a way of keeping parents in the loop. I put the main lesson content along with the homework task, and a short description of what parents can do at home to further support their child learning English. Not too much detail is required, and in fact I always prepare mine when I’m planning the lesson, so if I’m not sure how much of the lesson I will get through I play it safe and stick to something I know I will cover. I can always add things to the next lesson summary if I miss something important. I use these for all early years and primary students, but they work particularly well for the younger students up to the age of about 10. Older students are more capable of remembering and telling their parents what they learnt, particularly if you use Assessment for Learning strategies such as WALT, or Can Do Statements. I give out my summaries as the children leave the classroom, that way they make it straight into the hands of their parents instead of disappearing into school bags never to be seen again.

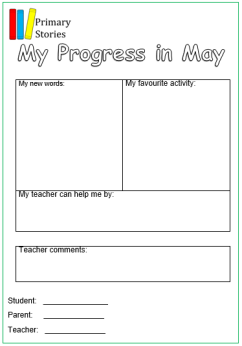

- Monthly portfolios

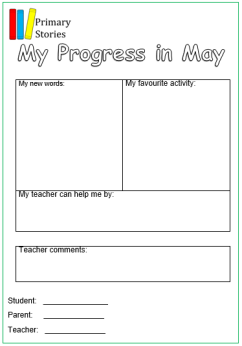

Something interesting happens when students know you have a way of contacting their parents. I don’t like to use the whole ‘Do you want me to contact your parents?’ threat because unless you follow it up it is fairly useless, and in following it up you give yourself (and potentially your colleagues) a lot of work. When I introduced monthly portfolios (download here ) it was a way of getting my students to reflect on and celebrate what they had learnt. It was also a way for me to get feedback. It works excellently in those ways, but it is also a good way to keep in touch with parents and again show them the value in their child’s lessons. Each month I choose 3 different criteria to reflect on, such as new words I learnt, my favourite topic, the funniest moment, my new skill, my best piece of work, how my teacher can help me, my ideas for next month. Students fill in the boxes by writing and/or drawing, and I collect them all in to comment on. Once I’ve commented, the students take them home, show their parents who sign and bring it back to me. It is also signed by the student before being stuck in their notebook. ‘Do you want me to contact your parents?’ turns into ‘remember I’ll be commenting on your portfolio soon’ and the students know you mean it. It’s a routine and easy way to increase communication with home in a non-threatening way.

Something interesting happens when students know you have a way of contacting their parents. I don’t like to use the whole ‘Do you want me to contact your parents?’ threat because unless you follow it up it is fairly useless, and in following it up you give yourself (and potentially your colleagues) a lot of work. When I introduced monthly portfolios (download here ) it was a way of getting my students to reflect on and celebrate what they had learnt. It was also a way for me to get feedback. It works excellently in those ways, but it is also a good way to keep in touch with parents and again show them the value in their child’s lessons. Each month I choose 3 different criteria to reflect on, such as new words I learnt, my favourite topic, the funniest moment, my new skill, my best piece of work, how my teacher can help me, my ideas for next month. Students fill in the boxes by writing and/or drawing, and I collect them all in to comment on. Once I’ve commented, the students take them home, show their parents who sign and bring it back to me. It is also signed by the student before being stuck in their notebook. ‘Do you want me to contact your parents?’ turns into ‘remember I’ll be commenting on your portfolio soon’ and the students know you mean it. It’s a routine and easy way to increase communication with home in a non-threatening way.

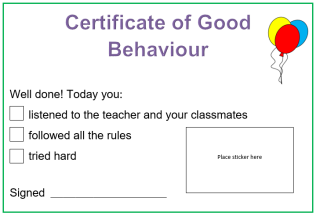

- Behaviour certificates

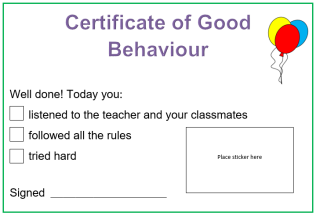

Sometimes certain students need a bit of extra motivation to keep on track in the classroom. I’m quite liberal with certificates, I have them for all sorts of things – helping my partner, working hard, arriving on time – whatever is needed. Children with behavioural issues, for whatever reason, often struggle to get generic rewards such as these, or stickers or points depending on what system the teacher uses. One of my favourite ways to keep a problematic child on task is by introducing a behaviour certificate, which I personalize for the child in question by writing specific achievable targets. To set up in class, I find a quiet moment at the start of the lesson to show the certificate to the child in question and go over the expectations. I usually ask the child how they are feeling and if they think they can meet the targets. If the targets are met during the course of the lesson, they are ticked off and the student chooses a sticker for the blank space and takes the certificate home. If I can’t tick all the boxes we keep it and continue in the next lesson. I have never had issues with jealousy or competitiveness from other class members, as children are usually very discerning and understanding. Someone being naughty is all part and parcel of being a child, and if someone needs extra reminding or help they tend to accept that. As long as they feel they are being fairly rewarded for their effort and contributions there shouldn’t be a problem. This one doesn’t relate directly to parental involvement, but certain children never get the rewards or the stickers, only nagging and complaints from the teacher. Getting a special certificate sends a very positive message to the child and the child’s parents. It shows that the teacher is offering help and acknowledging good work and progress. Download the template here

Sometimes certain students need a bit of extra motivation to keep on track in the classroom. I’m quite liberal with certificates, I have them for all sorts of things – helping my partner, working hard, arriving on time – whatever is needed. Children with behavioural issues, for whatever reason, often struggle to get generic rewards such as these, or stickers or points depending on what system the teacher uses. One of my favourite ways to keep a problematic child on task is by introducing a behaviour certificate, which I personalize for the child in question by writing specific achievable targets. To set up in class, I find a quiet moment at the start of the lesson to show the certificate to the child in question and go over the expectations. I usually ask the child how they are feeling and if they think they can meet the targets. If the targets are met during the course of the lesson, they are ticked off and the student chooses a sticker for the blank space and takes the certificate home. If I can’t tick all the boxes we keep it and continue in the next lesson. I have never had issues with jealousy or competitiveness from other class members, as children are usually very discerning and understanding. Someone being naughty is all part and parcel of being a child, and if someone needs extra reminding or help they tend to accept that. As long as they feel they are being fairly rewarded for their effort and contributions there shouldn’t be a problem. This one doesn’t relate directly to parental involvement, but certain children never get the rewards or the stickers, only nagging and complaints from the teacher. Getting a special certificate sends a very positive message to the child and the child’s parents. It shows that the teacher is offering help and acknowledging good work and progress. Download the template here

Teachers do have very heavy workloads, since the business of teaching is a very serious one. Clear and transparent communication with parents takes some of the responsibility and strain off. It can improve behaviour in the classroom, and increase the amount of support and language practice your students get outside the classroom. Additionally, parents love to know what’s going on with their children, and arguably have a right to know what they do in lessons. Why not try some of these strategies and see what works for you? I’d love to hear how you get on. Perhaps you have other ways of keeping in touch with parents in a positive and time-efficient way which you could share with us. If so please comment below.

I recently attended my first IATEFL conference in Brighton with one of the highlights being the Young Learner and Teens Special Interest Group (YLTSIG) Pre-Conference Event. The IATEFL conference is rich in expertise and knowledge and it’s a shame so few teachers can afford the time and money to attend. With that in mind, I was delighted to be asked to review the YLTSIG PCE, which I hope summarises the key learning and takeaways from the day. You can read my review

I recently attended my first IATEFL conference in Brighton with one of the highlights being the Young Learner and Teens Special Interest Group (YLTSIG) Pre-Conference Event. The IATEFL conference is rich in expertise and knowledge and it’s a shame so few teachers can afford the time and money to attend. With that in mind, I was delighted to be asked to review the YLTSIG PCE, which I hope summarises the key learning and takeaways from the day. You can read my review

Private English lessons are expensive so parents understandably have high expectations and want results. The age for learning a foreign language at school is getting lower and lower and English is seen as a priority to give children a head start in life. When parents know what their child does in class, there are two major benefits. Firstly, they have a deeper understanding of what to expect, e.g. their 5 year old is not going to be having fluent conversations in English after a couple of lessons. Secondly, a large majority of them actually want to help, and when parents practice lesson content at home with their child, there is much less work for the teacher. I always use lesson summaries, which you can download

Private English lessons are expensive so parents understandably have high expectations and want results. The age for learning a foreign language at school is getting lower and lower and English is seen as a priority to give children a head start in life. When parents know what their child does in class, there are two major benefits. Firstly, they have a deeper understanding of what to expect, e.g. their 5 year old is not going to be having fluent conversations in English after a couple of lessons. Secondly, a large majority of them actually want to help, and when parents practice lesson content at home with their child, there is much less work for the teacher. I always use lesson summaries, which you can download  Something interesting happens when students know you have a way of contacting their parents. I don’t like to use the whole ‘Do you want me to contact your parents?’ threat because unless you follow it up it is fairly useless, and in following it up you give yourself (and potentially your colleagues) a lot of work. When I introduced monthly portfolios (download

Something interesting happens when students know you have a way of contacting their parents. I don’t like to use the whole ‘Do you want me to contact your parents?’ threat because unless you follow it up it is fairly useless, and in following it up you give yourself (and potentially your colleagues) a lot of work. When I introduced monthly portfolios (download  Sometimes certain students need a bit of extra motivation to keep on track in the classroom. I’m quite liberal with certificates, I have them for all sorts of things – helping my partner, working hard, arriving on time – whatever is needed. Children with behavioural issues, for whatever reason, often struggle to get generic rewards such as these, or stickers or points depending on what system the teacher uses. One of my favourite ways to keep a problematic child on task is by introducing a behaviour certificate, which I personalize for the child in question by writing specific achievable targets. To set up in class, I find a quiet moment at the start of the lesson to show the certificate to the child in question and go over the expectations. I usually ask the child how they are feeling and if they think they can meet the targets. If the targets are met during the course of the lesson, they are ticked off and the student chooses a sticker for the blank space and takes the certificate home. If I can’t tick all the boxes we keep it and continue in the next lesson. I have never had issues with jealousy or competitiveness from other class members, as children are usually very discerning and understanding. Someone being naughty is all part and parcel of being a child, and if someone needs extra reminding or help they tend to accept that. As long as they feel they are being fairly rewarded for their effort and contributions there shouldn’t be a problem. This one doesn’t relate directly to parental involvement, but certain children never get the rewards or the stickers, only nagging and complaints from the teacher. Getting a special certificate sends a very positive message to the child and the child’s parents. It shows that the teacher is offering help and acknowledging good work and progress. Download the template

Sometimes certain students need a bit of extra motivation to keep on track in the classroom. I’m quite liberal with certificates, I have them for all sorts of things – helping my partner, working hard, arriving on time – whatever is needed. Children with behavioural issues, for whatever reason, often struggle to get generic rewards such as these, or stickers or points depending on what system the teacher uses. One of my favourite ways to keep a problematic child on task is by introducing a behaviour certificate, which I personalize for the child in question by writing specific achievable targets. To set up in class, I find a quiet moment at the start of the lesson to show the certificate to the child in question and go over the expectations. I usually ask the child how they are feeling and if they think they can meet the targets. If the targets are met during the course of the lesson, they are ticked off and the student chooses a sticker for the blank space and takes the certificate home. If I can’t tick all the boxes we keep it and continue in the next lesson. I have never had issues with jealousy or competitiveness from other class members, as children are usually very discerning and understanding. Someone being naughty is all part and parcel of being a child, and if someone needs extra reminding or help they tend to accept that. As long as they feel they are being fairly rewarded for their effort and contributions there shouldn’t be a problem. This one doesn’t relate directly to parental involvement, but certain children never get the rewards or the stickers, only nagging and complaints from the teacher. Getting a special certificate sends a very positive message to the child and the child’s parents. It shows that the teacher is offering help and acknowledging good work and progress. Download the template