Since going freelance I’ve been having problems defining what I do. Some days I’m a writer, others a conference speaker. I’m a teacher trainer and when I get the chance, a teacher. My non-teaching friends are mystified so I’ve gone back to referring to myself as a teacher to them. Professionally speaking my job title is getting longer and longer and therefore more and more ridiculous, and I need to find a snappy title which encapsulates the various things I do. I’m toying with going with Primary Guru, but that excludes all the work I do on CELTA and does seem a little grandiose, particularly considering I now do a fair amount of work from home in my pyjamas. Anyway, last week I was a writer. I love writing and I’m very much enjoying the project, but spending so much time writing for work meant I had no inclination to then spend my evenings writing for Primary Stories. This week, however, I’m zooming around Poland presenting at conferences and there’s nothing better than meeting teachers and listening to their ideas and opinions to get my blogging brain in gear.

If you live in Poland you’ll be aware of the upcoming structural changes to compulsory education. I’m presenting on the curriculum changes which impact primary teachers. Essentially there is a new core curriculum which emphasises amongst other things developing the ‘whole child’ via a holistic approach to teaching, and ensuring children have a positive early experience of foreign language learning to build self-confidence, self-esteem and lay the foundations for successful future learning. If you want to know how to do that, then come along to one of my sessions.

I have spent a lot of time analysing the new curriculum, which is very specific regarding what a child should be able to do at each stage of their formal education. The new curriculum also highlights the need for children to be aware of the learning process, and to be able to self-assess. I think self-assessment is great, however, it seems to me that in order for teachers to successfully facilitate self-assessment, they first need to be confident in assessing the students themselves.

Having a detailed curriculum allows teachers and schools to build up a syllabus for each subject detailing the specific items students will have learnt by the end of their course. Without a syllabus, the task of measuring progress is tricky. Looking back over the many years I’ve taught at private language schools, I can’t actually remember ever seeing a syllabus. There was always a coursebook with a contents page detailing the skills, grammar and vocabulary covered in each unit, and all the schools had created a pacing guide to go with it stating how much of each book should be covered during a course. Using a coursebook as a syllabus is not necessarily bad, but what about if two teachers teaching the same level at the same school are using different coursebooks? Not a big deal as most books cover similar language points at each level anyway. So far so good, although there is a but. Compared to other languages, many of which have a large number of inflections, English grammar is relatively straightforward. Learning the various verb forms is not in itself challenging. It’s learning when to use them which is. Take the past simple. We can use it to talk about the past – I won a swimming competition when I was 6, but we can also use it in conditional sentences to talk about the future – if I won the lottery, I’d buy a new car. We are not referring to a particular failed attempt in the past but alluding to the slight but real possibility that we may win the lottery in the future. Introducing the different usages gradually is absolutely the correct thing to do. The problem lies in the way we articulate what is being learnt. Look at a beginner A0 level coursebook contents page and you will see a unit on the past simple. Look at a CPE C2 level course book and it’s still there. The problem with using a coursebook as a syllabus is that if a student learns the past simple in their first English course, why are they still learning it 10 years later as an advanced student? We know it is different, but how do we successfully and helpfully communicate with students exactly what they have learnt and what still needs to be learnt?

It’s worth thinking about vocabulary too. English has a very large active vocabulary and as such many students struggle more with lexis than grammar. Again, there is some continuity across published materials in terms of what types of words are appropriate at each level, but since most books introduce vocabulary through texts there is a reasonable amount of variation. We often see towns and cities in B1 level coursebooks, but where one teaches cosmopolitan, industrial and spectacular another teaches provincial, vibrant and polluted. Again, variation is no bad thing, each teacher naturally tailors lessons and the material they cover to the needs of their particular students. The problem lies in how we communicate progress to students.

In a world where everything has to be measurable, how are we actually measuring our students? When teachers are asked to use continuous assessment and implement student self-assessment, what guidelines and training are they being given? Is self-assessment done badly better than no self-assessment or is it just a waste of precious class time?

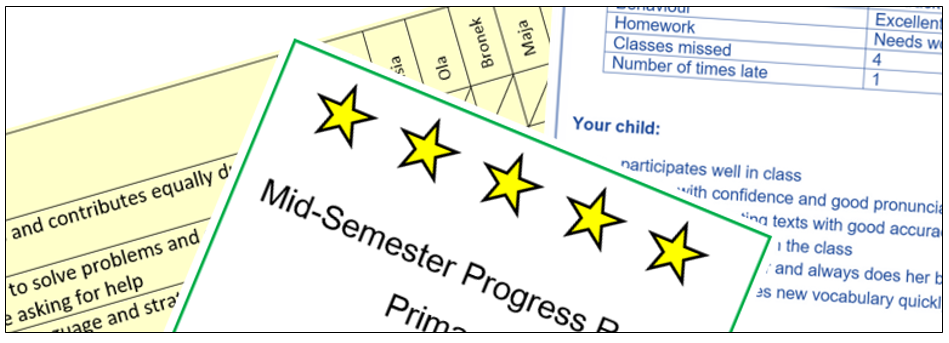

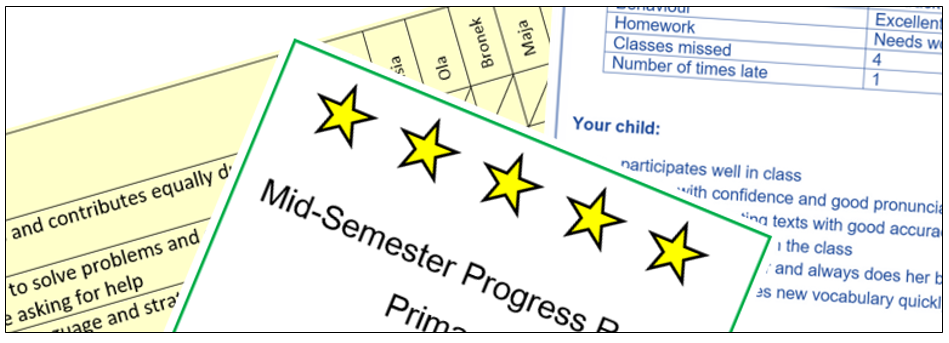

I decided to look back on what input the average TEFL teacher gets on assessing students. CELTA courses are required to include a session on assessment. My session looks at what makes a test good or bad, moving on to familiarisation with Cambridge exams. Both CELTA and Delta include input on conducting feedback, but the emphasis is on conveying answers and upgrading student language during the course of lessons. Trainees on CELTA and Delta are required to participate in group feedback and comment on other trainee’s lessons which is very useful and great practice. But in these cases they are concentrating on one teacher and have specific observation tasks to direct them. When working as a full time teacher I had 8 groups with around 12 students per group, so it was close to 100 students, and three times I year I was required to write reports for them. Some students were remarkably easy to write about – the high flyers and the little monsters. Most students, however, ended up with very generalised comments such as he participates well in class, and she would benefit from completing homework tasks on time.

When I was a CELTA trainer in training, affectionately known as the TiT, I spent every day for two whole months learning how to give feedback to trainees. I learnt what to look for, what to prioritise, how to structure written feedback and how to deliver oral feedback to benefit each individual on the course. It’s not just about knowing whether a lesson is good or not, it’s knowing how to best reach a trainee by taking their individual needs into consideration. Do they need a confidence boost? Will they respond better to direct feedback or a more softly softly approach? Is the feedback constructive enough that the trainee can move forward or do you run the risk of making them feel demotivated and unsure how to proceed? It’s not easy.

The first step towards giving meaningful feedback is gathering pertinent information. When you see students for as little as 2 or 3 hours per week it’s only natural that the task of teaching takes priority, and keeping track of individual student progress takes a back seat. So how can we build up a comprehensive picture of each student’s strengths and weaknesses when dealing with such limited time? In my last school, teachers were required to keep a record of grades throughout the semester for the four skills, grammar and vocabulary. Continuous assessment, rather than basing everything on an end of year test, is widely recognised as good practice. But simply writing down grades didn’t really help me when it came to writing reports and giving useful feedback to parents. All it really told me was whether or not a student was strong or weak in each area, resulting in report comments such as he is good at listening but needs to develop his reading skills. What use is that to any student or their parent? Which skills are we referring to? Are there any strategies the student needs to develop? Which ones? As I said there are countless benefits to using continuous assessment, however, this particular manifestation did not go far enough. What helped me was giving myself a few specific questions to focus on where students were, and what they needed to do to improve. I kept these questions in my register and focused on a couple of students each week, although it very much depended on the lesson. Sometimes there was plenty of breathing space for me to monitor closely and keep a record, other lessons required a much more active teacher role and I’d leave assessment for another day. Only focussing on a few students at a time reduces the tendency to simply compare students to one another and instead analyse each student within the context of his or her own individual learning. I also found I became much better at noticing what was going on in my classes and was naturally much more engaged with every student, not just the strongest most active or those with demanding behaviours. I was able to assess each student ‘formally’ 4 or 5 times during a semester, but this focussed observation also led to me being a better judge of the effect of my lessons on students, and inadvertently to improved teaching and learning.

Here are some questions which helped me, and I hope you can use them as a starting point:

- He/she participates and shows interest in lessons

- He/she tries to solve problems and complete tasks before asking for help

- He/she listens and contributes equally during pairwork

- He/she uses language and strategies covered during the course

There is nothing new about this form of monitoring, but what is helpful is to analyse what this information tells us. Question 1 gives us clues about student motivation and how active they are in the learning process. Taking a more active role in lessons would be good advice for a seemingly disinterested student, as well as looking at what you can do to involve that student more, by building in to lessons topics, tasks and activities which appeal to them. Question 2 gives information on independent, or autonomous learning. We want students to develop problem solving skills and to rely on their own instincts, but never asking for help can also be detrimental. Students need to discern when help is needed, and decide the most appropriate place to find that help. Question 3 tells us about a student’s communicative competency. When teaching skills, we tend to have one main aim in mind, the students may be getting a lot of speaking practice but in a listening lesson the ultimate goal is to improve students’ listening skills. In real life, listening and speaking are inextricable. When assessing question 3 we are engaging not only with the amount of participation, but also with a whole range of skills – the ideas being presented, knowledge of turn taking, topic management, coping strategies, repair and so on. In a world where we emphasise learning to learn, question 4 helps us evaluate how well students use the recommended strategies. Some students love reading, others hate it. Some are good and some struggle. As foreign language teachers our goal is not to teach students how to read, it’s to teach them how to do it better in a foreign language. Grading students according to whether or not they are good at reading is not helpful, but looking at how they use strategies is. With this information we can make helpful and practical suggestions.

Gathering this sort of information, I would argue, makes the business of reporting student progress much easier. It contributes to pragmatic, personalised and helpful feedback which will help students move forwards with their efforts rather than simply looking back at what was good and bad about the past semester. After all, as the British Council will tell you – It’s all about the future!

While many people in Lebanon are truly multilingual, everyone here is plurilingual. Broadly speaking multilingualism refers to the knowledge of a number of languages. Plurilingualism, on the other hand, is concerned with the use all the linguistic resources available to a person in order to communicate. Therefore we are all unavoidably plurilinguals. In a multilingual society, different languages coexist. In a plurilingual society different languages interact and interrelate with each other, with users drawing on their whole linguistic repertoire to communicate. My drama at the supermarket took place in English, French and Arabic and while all the participants didn’t share a common language, we effectively solved my problem of how to get home. In a true pluricultural environment no one language is given precedence over another, and since language is so closely linked to culture it is one which promotes multiculturalism, understanding, respect and acceptance.

While many people in Lebanon are truly multilingual, everyone here is plurilingual. Broadly speaking multilingualism refers to the knowledge of a number of languages. Plurilingualism, on the other hand, is concerned with the use all the linguistic resources available to a person in order to communicate. Therefore we are all unavoidably plurilinguals. In a multilingual society, different languages coexist. In a plurilingual society different languages interact and interrelate with each other, with users drawing on their whole linguistic repertoire to communicate. My drama at the supermarket took place in English, French and Arabic and while all the participants didn’t share a common language, we effectively solved my problem of how to get home. In a true pluricultural environment no one language is given precedence over another, and since language is so closely linked to culture it is one which promotes multiculturalism, understanding, respect and acceptance. Language is ever present in Beirut. As you know I speak neither Arabic nor French, however, navigating the city is not as challenging as might be expected. For example I can ascertain lots of useful information from the pictured sign. I know it’s a tourist attraction from the colour and style. I can see it is a Christian church from the picture. I know how to get there from the arrows. I can guess there is a meeting room, and a place to get information because there are similar words in English. We tend to take it for granted that students will develop the necessary skills of inferring information on their own. However we also know that certain children are regularly completely lost in lessons however well we think we have set up the task. These children tend to become the banes of our lives, and we forget the emotional and social burden this lack of understanding puts on them, let alone the effect on their academic development. Remember to ask yourself if you have provided enough scaffolding, clues and help to allow all children to succeed even though it may seem obvious and old ground.

Language is ever present in Beirut. As you know I speak neither Arabic nor French, however, navigating the city is not as challenging as might be expected. For example I can ascertain lots of useful information from the pictured sign. I know it’s a tourist attraction from the colour and style. I can see it is a Christian church from the picture. I know how to get there from the arrows. I can guess there is a meeting room, and a place to get information because there are similar words in English. We tend to take it for granted that students will develop the necessary skills of inferring information on their own. However we also know that certain children are regularly completely lost in lessons however well we think we have set up the task. These children tend to become the banes of our lives, and we forget the emotional and social burden this lack of understanding puts on them, let alone the effect on their academic development. Remember to ask yourself if you have provided enough scaffolding, clues and help to allow all children to succeed even though it may seem obvious and old ground.